Woodland Indian Clothing is a topic that many historical reenactors enjoy getting more information about. I have researched this subject for decades and wrote the first book about it back in 1987 called "Indian Clothing of the Great Lakes, 1740-1840." There has been a lot of research done since then and my next publication after "Native Indian Ingenuity" is complete will be about this topic. I have launched a new shop on Etsy

http://craftinghistory.etsy.com that features some 18th and 19th century cloth clothing including Shirts and breechclouts.

The 18th century trade shirts are two distinct periods. The India print cotton shirts are clearly made from cloth that was available beginning in the 17th century and well into the 18th century. This bold prints are recreated today in India and south Asia for export to Europe, the USA and worldwide. Fortunately, they are based on many of the original designs and are large pieces that are marketed for bedspreads and coverlets so they are perfect for getting even an extra large size shirt out of each one. The shirts are sometimes embellished with ruffled neck and cuffs but are equally authentic without. As silver trade brooches became popular and abundant, they were pinned on the front, shoulders and bottoms of the shirts. I have two of these listed as lightly used and in XL for that special someone who needs a little more breathing room.

The next category is the cotton chintz fabrics that were manufactured in Europe. When the importation of Indian prints and other Asian fabrics was outlawed in the mid-18th century, it was then up to the textile manufacturers to print fabrics that had been popular among the masses. Particularly the French and then the British made attempts to print textiles to equal or surpass the popularity of the Asian prints. These were then exported to the New World and gained popularity with the Native Woodland Indians and those on the prairies. Most settlers, merchants, politicians and the like wore a similar style but very subdued white, off white and certainly not the bright, gaudy colors that the Native populations preferred. The French marketed the new fabrics by wearing them in the wilderness and having Native women make shirts up and trade them as finished garments to still other Native people. It was not unheard of to wear floral prints, stripes and polka dots all in the same costume among the French fur traders and voyageurs.

The early 19th century saw changes in clothing among the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley Indians, particularly when the Shawnee Prophet spoke out against the use of "white man's trade cloth" in favor of ancient Indian traditions. There was for a very short time, from about 1809-1812 a brief resurgence in the buckskin or leather garments from ancient times. There are textual references to Tecumseh and his men riding out to garner support for their cause wearing "black" dyed leather leggings, shirts and moccasins. The Prophet encouraged the Native people to go back to the "old ways." The problem was that it had been several generations since most of these people depended on brain tanning and sewing leather into fitted garments and the results were less than perfection. There are two such "outfits" that survived and were featured in the Ruth Philips publication "Patterns of Power" back in the 1980's. They showed crudely stitched shirts with military style"epaulettes" on the shoulder. This was clearly an imitation of a military frock seen or even used by the maker of the garment. The leather leggings were equally crude in design and stitching as if a child had made such for their very first project.

The fact that hunting grounds and habitat was diminishing, reliance on trade goods was the norm and that not every individual Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa or other tribal member followed these ideas, offers some explanation as to why this fact gets little attention in recreating the era of the War of 1812. The fact that politics played a vital and substantial role in the lives of all the Natives of that era is evident in the fact that some followed the ideals spread by the Shawnee brothers and still others adhered to a type of Catholic belief long instilled in them by the influence of Jesuits and other Catholic teachers, such as nuns and missionaries of the 18th and 19th centuries. This too is reflected in a clothing style that appeared around this time period.

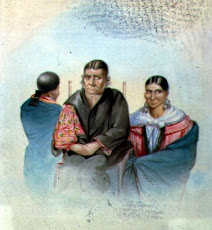

The style had more to do this time with women. There are capes being added to the more traditional drop-sleeved trade shirt. These decorative capes came in several styles. The one that seems to be the most elaborate was found at the Cranbrook Institute in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. I found this in a drawer by accident after having asked the curator about the blouse and was told that he was not aware of any such garment. The first time I had any hint that such a thing existed is when I worked at Historic Fort Wayne in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1980-83 and several slides came into my possession that showed a dark colored blouse or shirt tacked to a wall with the cape spread wide making it appear like a giant bat-like creature rather than a rare treasured museum piece from the mid-19th century. I did some research on it and came to find out that it had a Wabash area provenience and was labeled as being made by a Miami. Looking at portraits of Miami and Potawatomi women artistically rendered by George Winter in the 1830's, it was clear that this seemed to be a popular style worn in that era. It was not exclusive as the older style was still depicted as well as a more fitted garment, probably a version of a short-gown.

These fashions will be discussed and visually displayed in the new book, "Eastern Woodland Clothing" when it comes out in a couple of years.

Check out the etsy site for some great bargains on gently used clothing and for prices on the Caped Shirts and breechclouts. Check back often for more great Native Woodland Indian Clothing Selections.

http://craftinghistory.etsy.com

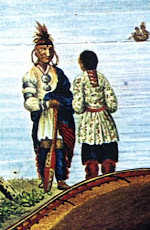

Skirts of the 18th century era were of varying lengths. If you look at some of the mid-18th century portraits that show Native women such as Huron, the skirts appear no longer than just above or on the knee. By the 1830's the portraits show the length of the skirt appearing mid-calf to ankle length. This may follow the trend of Euro-Americans in their fashions to a degree, especially in the 19th century when the Indians were living in and among the white settlers of the conservative beginnings of the Victorian era.

Silk ribbons were attached to hems of skirts in concurrent rows from the hem upwards. These may be of one color or several. The widths of the silk ribbons ranged from 1/2" up to 1 and even in some rare instances perhaps 2" in width. These were sewn on with metal needles and silk thread which arrived via the fur trade. By the end of the 18th century a new dimension was beginning to show up in the use of silk ribbons. The ribbons were being sewn on in layers and cut, folded and stitched in geometrical shapes and patterns. These seem to be reflective of the earlier designs seen in porcupine quillwork on bags, pouches, knife sheaths and moccasin flaps.

The ribbons were meticulously applied and the work continued well into the 19th century. The silk ribbonwork shows up on a wedding ensemble on moccasin flaps as well as the hem of a skirt as early as 1802 among the Wisconsin Menominee.

The Miami, Potawatomi, Lenape and other Great Lakes tribes also showed an inclination toward this type of embellishment. It was not just worn for special occasions but seems to be used frequently on everyday clothing as well. George Winter, in his time with the Miami and Potawatomi in Indiana noted the use of such elaborate embellishment on clothing worn by Frances Slocum, a white captive and her two daughters then living on the Wabash near Peru, Indiana.

The skirts were made from wool trade cloth, often dark blue or red stroud cloth. The stroud cloth originated as "blotter" cloth in Stroudwater, England. It was used to absorb the inks and dyes when other fabrics were above drying. This cheap cloth became popular among traders and it along with "halfthick" and other wool fabrics and wool blankets replaced any sign of earlier textiles such as plant fiber or even leather used for skirts.

Leggings also appear to have been made from the same selections of wool. Wing flaps on the outside of each leggings would get wider as time went by. These too served as points of embellishment and were frequently edged with white beadwork and silk ribbons. The ribbonwork became more elaborate and designs grew in size and floral patterns were added during the post-removal period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

For more information on Native Woodland Clothing of the fur trade/colonial era, check back for more posts and feel free to contact me. (812) 825-1234